William

Eggleston

William

Eggleston

(1937-)

Documentary, Fine Art

|

Biography: By Stanley Booth

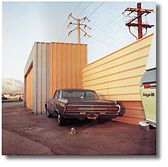

Sept. 7, 1999 -- William Eggleston, now 60 years old, seems securely

attached to the title "Father of Color Photography."

Maybe the word "color" should be modified by "art"

or "artistic," because of course he didn't invent the

process. There have been those, however, who would deny that Eggleston's

photography has much of anything to do with art.

I met Eggleston in Memphis in the early '60s, shortly after he

had come there from his native Mississippi. He was already reputed

to be a "serious" photographer. His progress over the

decades, however slow and frustrating it's seemed at times to

him, has been astonishing. The prince of a matriarchal Southern

empire (his mother, two sisters, one wife and many female admirers),

he has moved with assurance all along, paying scant heed to naysayers.

One afternoon in 1967, Eggleston, a beautifully groomed and attired

young man with dark hair and eyes, dropped in on John Szarkowski,

then curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art, with

a suitcase of color slides. It was as if Eggleston was turning

himself in to the authorities. A result of this meeting, nine

years later, was Eggleston's one-man show of color photographs

at the MoMA, only the second in its history. In his introduction

to "William Eggleston's Guide," a hardcover book published

by the museum to accompany the show, Szarkowski referred to Eggleston's

pictures as "perfect," to which the highly offended

New York Times art critic Hilton Kramer responded, "Perfect?

Perfectly banal, perhaps. Perfectly boring, certainly."

The MoMA show included such images as a dog drinking from a mud

puddle, shoes under a bed, a child's tricycle, a tile shower and

a kitchen oven. Maybe Kramer figured if he wanted to see a pile

of shoes, he could look under his own bed. Others have objected

to the subject matter of Eggleston's photographs -- one compared

Eggleston's work unfavorably with Ansel Adams' big shots of such

things as moonlight on mesas. Adams' subjects are magnificent

but have little to do with most people's daily lives. Eggleston's

work is dedicated to showing the beauty, humor and horror that

surround us at all times and in all places.

An important key to Eggleston's underlying meaning is his admiration

for Paul Klee and Vassily Kandinsky. As did these two good-humored

masters, Eggleston produces works that are at once, in his phrase,

"like jokes and like lessons." It would be a mistake

to overemphasize the influence of Klee and Kandinsky on Eggleston

-- even calling it an influence goes too far. It's more of an

affinity, comparable to the one he shares with musicians as disparate

as Satie and Ketelby. (Eggleston is also a musical composer and

performer, but that's a topic for another day.)

Growing up in comfortable circumstances on a cotton plantation

in Sumner, Miss., Eggleston took his first pictures when he was

around 10, using a focus-free snapshot camera, the Brownie Hawkeye.

"Everything I photographed blurred, looked horrible,"

he remembers.

Eggleston's father died in the Pacific during the Second World

War, and much of Eggleston's nurturing consequently fell to his

maternal grandfather, Judge Joseph Albert May, who died when Eggleston

was 11. "He took pictures for a hobby, so I had his Contax

and Leica IIIA at home," Eggleston says.

Eggleston attended a military-style boarding academy, Webb School

in Bell Buckle, Tenn. His memories of the place are not pleasant:

"One of the older students used to tell me, 'Eggleston, I

don't know whether to call you "shit-tit" or "tit-shit."'"

But he had a friend there named Tom Buchanan, who, later, when

they were both attending Vanderbilt University, "marched

me to the store and made me buy a camera and developer."

In the words of the brief biographical sketch in the "Guide,"

Eggleston "matriculated at, and on occasion attended, Vanderbilt

University, Delta State College, and the University of Mississippi."

At Ole Miss, around 1962, he saw for the first time the work of

Cartier-Bresson, his initial inspiration: "A photographer

friend of mine bought a book of Magnum work with some Cartier-Bresson

pictures that were real art, period. You didn't think a camera

made the picture. Sure didn't think of somebody taking the picture

at a certain speed with a certain speed film. I couldn't imagine

anybody doing anything more than making a perfect Cartier-Bresson.

Which I could do, finally."

More on William Eggleston:

•Salon.com

- Brilliant Careers

Features Articles and Examples of Eggleston's Work.

•William

Eggleston: 2 1/4

Several Examples of Eggleston's Work.